We asked Scott Stickland, a senior business analyst at CCC’s subsidiary, Ixxus, to share some personal experiences from his work with clients on digital transformation initiatives. The second in a series, Scott talks about the considerations of process improvement.

Ask the Right Questions to Improve Your Processes

Digital transformation has four key factors that should always be considered in unison, to maximize the chances of success. These factors are Content (see the previous post here), Process (this post), People and Technology.

When we talk with our clients, Process often causes the most confusion. This is because process typically gets used in the same context as ‘workflow’ and ‘status,’ and clients often assume it’s related to the technological side of things, i.e., an IT system process, rather than a more human concern. Let’s refer to the Oxford English Dictionary definition of process:

process /ˈprəʊsɛs/ noun

a series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end.

The steps taken by an organization to achieve a specific result is what we consider a process. These steps will include the People that are involved, the Content that they are moving through the process, and the Technology they use.

As a Business Analyst, the typical question I ask clients around process is “Why do you do that?” The answer that always rings alarm bells is “Because that’s the way we’ve always done it.” Even when a client doesn’t use those exact words, it’s usually pretty easy to read between the lines and end up with the same answer.

The alarm bells sound because the answer implies that a). The process hasn’t been reviewed for a long time, and therefore may no longer be fit for purpose, and potentially, and even worse, b). No one knows why something is being done in a particular way, or even being done at all!

Scenario b is surprisingly common and is especially prevalent in organizations with a high turnover of staff.

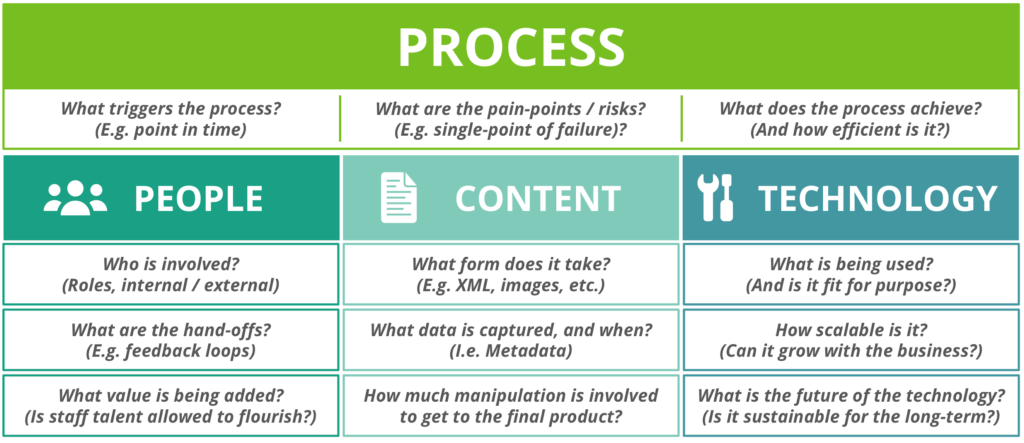

Fig. 1. A typical breakdown of the questions that need consideration when exploring Process.

When looking to improve a process, it’s essential to keep the following three process change success factors in mind:

- People are critical to the process. People have the power to reject changes to processes (either openly, or by stealthily reverting to old ways of working), and changes should always be designed to work across an entire organization.

- Process Improvement is not a single event. It should be considered as a constant review of how an organization achieves its goals, and as such requires long-term investment.

- Process documentation should always be kept up-to-date (but is often ignored). Having an accurate description of a process, including answers to the sorts of questions highlighted in Fig. 1, will mitigate against tacit knowledge being lost when staff leaves. Up-to-date process documentation also helps to support adoption, facilitate efficient process reviews (including identification of risks/opportunities), and can also be used to inform executable workflow models, where diagrams can be interpreted by a workflow engine to drive systematic behavior.

The Flawed Process

One process that was in place at the time I joined involved printing vast amounts of hard copy proofs that were marked up by hand and then couriered to a team of typesetters in India. The typesetters would then make the updates to the content, and send the hard copies back by courier, marked up with questions.

Improvement Attempt #1: Technology

Initially, I tried to introduce electronic markup via PDFs but soon realized that this level of change would not be sustainable and would also severely impact production times during the initial learning period.

Improvement Attempt #2: Content and Technology

So instead, I looked a little further down the chain and implemented the change to scan the hard copy markups and transfer them electronically, as we already had the under-utilized technology to support this change. Instantly, we were saving money on the cost of paper, ink, and couriers, not to mention time (the average courier time was two days). However, cracks quickly started to appear as I found out that the typesetters in India were printing out the scanned markups, hand-writing their questions, and using couriers to send the hard copies back to the editors in the UK.

What I had Missed: People

What I hadn’t fully understood was the method for which the typesetters would implement the changes to the content while using the scanned markups. They were used to having the hard copies on display while they inputted the edits. With the scans, they had to flip between applications on their monitor, i.e., remember the changes that needed inputting by looking at the scans, and then flip applications so that they could edit the content accordingly.

The Success Factor

What I missed brings me back to my first ‘process change success factor’ above, about people – always make decisions about changes to process ‘from the shop floor.’ This mantra was pioneered by Kiichiro Toyoda, founder of Toyota Industries. His insight from the late 1930s is still as relevant today as it ever was.

It’s true that strategic company goals and objectives can be successfully formulated at a boardroom level. However, when it comes to the everyday processes that form the basis of an organization’s core outputs, rolling out changes without the proper level of engagement from the people that will be performing the process means you’re likely to fail.

In my scenario, once I understood the challenges faced by the typesetters, I was quickly able to conduct some benefits analysis that predicted the cost-savings by switching to working purely with the scanned markups and put together a successful business case to purchase a second monitor for each of the typesetters. The typesetters saw this investment as a huge sign of the organization’s gratitude for the work they did and were therefore much happier to mark up the digital copies with their questions for the editors.